(Photo by Ed Robertson on Unsplash)

After a bit of a fallow period for short story reading last year, I maxed out this year with some wonderful collections.

Reverse Engineering is a series of books from newbie publisher Scratch Books and is based on a simple but wonderful concept: a set of classic contemporary stories alternating with interviews with their authors about their craft. Writers such as Sarah Hall and Chris Power give invaluable insights into their writing process. The second book in the series is on my Christmas list.

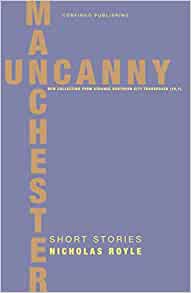

Nicholas Royle’s Manchester Uncanny (Confingo) is the second in a trilogy of collections exploring the mysterious and eerie corners of three cities (following London, and with Paris to come). Royle draws skilfully on Manchester’s geography and heritage, including a story based on Joy Division’s first album, Unknown Pleasures. A compelling collection.

I’ve long wanted to master the art of writing flash fiction but usually fail miserably. Nick Black’s collection of (mostly) flash pieces, Positive and Negative (AdHoc), is a terrific example of the genre. There was also a welcome new collection this year from Amanda Huggins – An Unfamiliar Landscape (Valley Press) features her excellent Colm Tóibín award-winning story ‘Eating Unobserved’. I also really enjoyed collections by Chloe Turner (Witches Sail in Eggshells, Reflex Press), Jamie Guiney (The Wooden Hill, époque) and Ben Pester (Am I in the Right Place?, Boiler House).

In non-fiction, there were three standout books. The Passengers by Will Ashon (Faber) is a remarkable work of contemporary oral history: Ashon interviewed dozens of people all around the UK, and their voices bear witness to what it means to be alive today. Michael Pedersen’s Boy Friends (Faber) is a lyrical and moving exploration of male friendship – a tribute to Scott Hutchison, the singer-songwriter who died in 2018.

For a number of years, the Times journalists Rachel Sylvester and Alice Thomson have jointly interviewed public figures. Their fascinating book, What I Wish I’d Known When I Was Young (William Collins) draws on these interviews to investigate how adversity in childhood can influence adult life.

Fiction-wise, I was greatly impressed by Ashley Hickson-Lovence’s Your Show (Faber), which tells the story of football referee Uriah Rennie. Set in Stone by Stela Brinzeanu (Legend) is a beautifully written tale of love against the odds, set in medieval Moldova but with contemporary resonances. Zoë Folbigg’s The Three Loves of Sebastian Cooper (Boldwood) is a page-turning story of three very different women as they gather at the funeral of the man they all loved.

I was hugely excited to learn that Louise Welsh was publishing a sequel to her brilliant novel The Cutting Room, and it didn’t disappoint. The Second Cut (Canongate) takes us back to the seedy Glasgow world of auctioneer Rilke in another superb literary thriller. Last but definitely not least, I loved Janice Hallett’s The Twyford Code (Viper), an ingenious crime novel told almost entirely through transcribed audio files.